Internet Service Providers selling out customers’ privacy is awful, old news

On April 3, 2017, Trump did what no one asked for, except for an army of telco lobbyists: he quietly signed an order from Congress to explicitly allow ISPs to sell users’ browsing history without users’ permission. There was no photo shoot or fanfare: it was too depressing and impossible to explain to the American people… US citizens had just been sold out by their politicians.

It was another page from ISPs’ long history of monetizing users’ internet traffic in the US. From hotels and airlines injecting ads into browsing sessions via WiFi hotspots, to cell carriers (like Verizon and AT&T) selling ad data based off your mobile traffic, to big ISPs and carriers pitching Wall Street on the idea that they could compete with Google as an ad company: when ISPs aren’t cashing out users’ privacy, they’re at least fantasizing about it.

That’s a major problem because Internet Service Providers, like AT&T and Comcast, have a sacred position as gatekeepers of all your internet activity. Because ISPs see the domains you visit (and what your devices’ apps connect to), the level of privacy at stake is staggering. Monetizing your data is bad, but their role in your life also gives law enforcement a juicy, easy target to serve with National Security Letters (or lesser subpoenas), which compel disclosure of your information. Thanks to something called the 3rd-party doctrine, police don’t even need to use a conventional search warrant (from a judge) to ask ISPs for info about you. Recent reports also show that an increasing percentage of such requests come with a gag order, despite increasingly weak justifications for doing so. This means ISPs that are served with subpoenas often can’t even tell you they’re giving up your info. Truly awful stuff. Even if our rights against frivolous searches aren’t protected in law anymore, they are still American values, and they are worth resurrecting, if possible.

ISPs should, at every turn, be deprived the ability to collect personal data in the first place. That is a very tricky thing to pull off, but other solutions exist: Tor and VPNs shield significant amounts of user data from ISPs including internet traffic. That’s great! But most people don’t avail themselves of those options, and they have drawbacks (more on that later). Apple is entering the fray with a novel offering called Private Relay, and it will change everything.

What is Apple’s Private Relay?

First, I recommend watching Apple describe iCloud+ Private Relay in its own words. Here’s the two-minute segment from WWDC where they announced it, and here’s a session on the topic they produced for developers.

Private Relay is an opt-in feature debuting in iOS 15, iPadOS 15, and macOS 12 Monterey that’s available to everyone who pays for iCloud storage (even the $1/month tier). That is a lot of people. Users can begin testing the feature by installing a beta OS release on one of their Apple devices.

Once you enable the feature, all of your Safari web traffic on your device will be encrypted in such a way that “no one can intercept and read it”. It accomplishes this by sending all requests to “two separate internet relays” in a system “designed so that no one —including Apple—” can know both who you are and what site you’re visiting. It also gives DNS queries from your device and unprotected app traffic the same, privacy-protecting treatment.

When you connect to a website using Safari, the site’s server will not see your device’s IP address but rather a generic IP address from one of Apple’s proxy partners in your “approximate” location. You can also choose to use an IP from a “broader location” to even further preserve your privacy. While that’s what the server you’re connecting to sees, your ISP will only see that your device is connecting to Apple’s servers. ISPs no longer get to see what sites you’re trying to visit.

What a claim! Apple is saying ISPs won’t know about your internet traffic if you use Safari on a device with Private Relay. Not even Apple’s CDN partners, who carry out the second stage of the “dual hop”, will know who you are, thanks to clever engineering.

Hats off to Apple’s architects. At first glance, the principle behind this “dual hop” seems inspired by Tor, a browser that “directs Internet traffic through a free, worldwide, volunteer overlay network” with an encryption scheme that promises to “conceal a user’s location and usage” from prying eyes. The main issue with Tor has always been that it’s slow. Apple claims Private Relay works “without compromising performance”. There are reasons to be very skeptical of that claim by Apple (more on that later), but nevertheless, Private Relay will certainly be far faster than using Tor. Finally, Tor has also been facing some network security issues as of late. Tor is still a massively important project for dissidents in oppressive countries. Everyone, especially Apple employees, should consider pitching in to the Tor Project, as Private Relay will not be rolled out in the regions that arguably need this privacy the most, but will likely take some wind out of the sails of the Tor project.

Ok, but how does this differ from your run-of-the-mill VPN?

It’s similar in some ways, but a VPN company can see a far more complete picture regarding your internet traffic than Apple can with Private Relay. Apple claims to have built a system where it can’t even be tempted to peer into your traffic.

VPN companies are rightfully scared about Private Relay. Basic Google search results about Private Relay currently offer up a bunch of “paid content” from VPN companies, only highlighting VPN’s advantages, which are, namely: VPNs can encrypt all traffic from your device, give you more control over what region your traffic surfaces in (so you could pose as a web user in, say, Vietnam with a VPN if you wanted to), and likely offer faster web traffic speeds than Private Relay.

If you’ve listened to a tech-oriented podcast in the past five years, you’ll know that VPNs heavily advertise on shows, and their pitch largely overlaps with Private Relay’s: browse safely from random places like a coffee shop and hide your internet traffic from your ISP. The issue is that the VPN company is itself a target for law enforcement. Just the other day, a company called DoubleVPN had its “servers, logs, and account information seized by law enforcement”. Even VPNs that claim to not log user data still physically could, because the tech allows for it. That makes them a juicy target for nationstate-sponsored malware as well. Private Relay prevents rich logging because, again, “no one —including Apple—” can know both who you are and what site you’re visiting. It’s an entirely different ballgame than a VPN for the average user.

But what about Google Fi (Google’s carrier/MVNO), which has offered a free VPN for years!? Well, it’s a great segway into:

Super special VPNs, two kinds of trust, and Apple’s scale

When it comes to Apple’s descriptions about how their tech works—I turn to their solid track record of transparency on their technical approach to security. For years, they have published first class whitepapers about systems like FaceID, their A-series chips’ secure enclave, and more, which have largely stood up to scrutiny by the industry.

If you believe Apple’s claims about how its “dual hop” system works, you shouldn’t have to trust Apple when it comes to handling traffic data from your Safari browsing. Private Relay works in a “zero trust required” manner, but not all of Apple’s systems do, such as how it stores iCloud iOS backups (unencrypted).

While many VPN companies claim to not log your traffic metadata, they still have the option to do so, because VPNs inherently give the provider all the necessary data to log. With these companies, you have to trust their behavior with data handling (even when police come asking for it or some new temptation to monetize it arises).

There are exceptional VPNs though. Take Google Fi (Google’s carrier/MVNO), which offers a VPN that uses its own unique scheme to give users privacy, by establishing each session with a unique one-time token that, it says, does not tie back to your identity. That’s excellent!

VPNs can absolutely be run in an above-board privacy respecting way, it’s just a matter of having to completely trust the operator.

Private Relay will be an available option for hundreds of millions of devices this Fall. It’s far more convenient than Tor and setting it up is way easier than your average VPN. This will lead to incredibly wide adoption (relative to VPNs and Tor) and give it a chance to change things on a societal level.

Using Private Relay will not be seamless

Private Relay will ruffle the feathers of ISPs and local network administrators.

This is a power move reminiscent of 1) when Apple launched the iPhone and decoupled phone software from the carrier, and 2) when Apple launched iTunes and CD-selling music labels had to come on board.

The industry will push back, leading to friction for consumers.

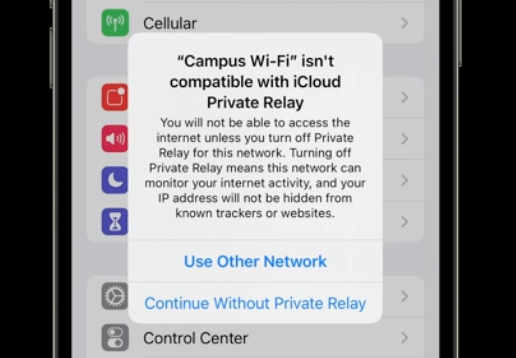

Many local area networks, such as WiFi on college campuses, will end up prohibiting Private Relay traffic. This will lead to inconvenienced users, who will be presented with dialogs to disable Private Relay for that network. I’m sure ISPs of all sizes will be tempted to also put in place hard blocks.

As a matter of fact, between writing the 1st and 2nd drafts of this article, reports began trickling in of T-Mobile blocking users with Private Relay enabled. Allowing this feature may become a big differentiator for carriers and ISPs. That said, Americans have far less choice on average when it comes to ISPs than Europeans, so “differentiators” don’t matter when your street address dictates your provider. It’s an American curse. 🇺🇸

At this stage, there are also reports of glitches where, if you live in a country without a nearby Apple “proxy” partner, your traffic can surface from an entirely different country. That will often break the web site you’re trying to visit. Hopefully (and I expect) Apple will keep adding proxy partners leading up to launch, and this situation will improve.

Furthermore, there are reports of bugs, even privacy compromising ones like this one from the infosec community. Especially while this software is in beta, don’t assume you have Tor-level privacy.

Serving all this traffic through Private Relay bottlenecks will likely increase the odds of service disruptions and traffic congestion. It is hard to say how well it will work this Fall when iOS 15 officially ships. As someone who has been using Private Relay for weeks, let’s just say I’m skeptical that performance won’t be “compromised” at all, as Apple claims. In fact, since the public beta of iOS has shipped, reports have surfaced of speed comparisons—and Private Relay appears to slow web traffic down a bit, which lines up with my experience—but it’s still in beta and I’ve loved using the service so far.

Where it won’t exist

Countries that don’t pretend to respect citizens’ civil liberties, such as China, Belarus, Saudi Arabia, and the Philippines, are draconian when it comes to inspecting citizens’ web traffic. In fact, China has banned VPNs altogether, even recently in Hong Kong. For years these countries have enshrined in law the right to spy on every part of their citizens’ lives.

Apple says it will not be offering Private Relay in China, Belarus, Colombia, Egypt, Kazakhstan, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Turkmenistan, Uganda, or the Philippines. Ouch. I would expect the list of unsupported countries to grow, but we’ll just wait and see.

But why? What is Apple’s plan to justify profiting in countries like this?

Apple’s CEO Tim Cook said at a Fortune event in 2017, when asked about its compliance with China’s censorship and problematic laws: “Each country in the world decides their laws and their regulations. And so your choice is: Do you participate, or do you stand on the sideline and yell at how things should be? You get in the arena, because nothing ever changes from the sideline.”

There are at least a few glaring issues with this stance:

- It sounds like the “you” in “Do you participate?” is referring to Apple, so it’s worth noting that Apple, as we know it in America, is not the Apple that is doing business in China. It’s a lesser, stripped down version of Apple, without key features like… Private Relay. As the New York Times reported, Apple even handed over legal ownership of its Chinese customers’ data to another company entirely. That’s certainly not Apple™️. Cook’s statement conveys things as though they were Apples to Apples, but it’s really apples to oranges.

- The spirit of the statement is only honest if it’s periodically reassessed to gauge efficacy. It’s been over three years: has Apple had positive effects in troubled countries? As they roll out laws that destroy press freedoms, deny recognition of entire groups of people, and prevent the recollection of key events in history? (Referring to Apple censorship of LGBTQ+ apps, the Taiwanese flag, and VPNs following the “National Security” law used to dismantle Hong Kong press freedoms, and more.) At what point do you recognize complicity? Is Apple even willing to consider that it can be complicit instead of a force for good? If it is, it should be made known. If not, the company’s stance holds no water.

- In his statement, Cook denigrates “stand[ing] on the sideline and yell[ing] at how things should be”.

That forfeiture of voice is a huge concession for the Apple community, including the company’s many employees, because, let’s face it: those of us born outside authoritarian countries are on the sidelines, and yelling is our primary tool in influencing US geopolitics. Cook basically says Apple can’t yell from the sidelines about unjust laws in countries if it also does business there. It checks out: Apple has had a relatively quiet workforce when it comes to employee activism (except on work from home policies). Maybe they should start yelling more about how their company is changing the world.

In summary, unless Apple presents a privacy-respecting Apple in troubled countries and periodically reassesses whether a fair society is prevailing there, then many of us would prefer “yell[ing] from the sidelines”.

The privacy benefits will truly be incalculable for the countries where it does exist

Let’s walk down memory lane. Do you remember where you were when the news broke about Snowden? I was in a McDonald’s with some terrible food that was fast approaching room temperature, as I sat, jaw-dropped, completely glued to The Guardian’s bombshell reporting.

Knowledge is power, or so they say, but the revelations of US spying on its own citizens morphed in a couple years from what seemed like a catalyst for change into a crushing status quo: surveillance normalized in a way that seemed irreversible.

AT&T already sells location and call data directly to police for enormous annual sums, to only be used in “parallel construction” of cases against people. AT&T is also one of the biggest ISPs in the US, and–to come full circle–as of 2017 has the explicit right to sell users’ web traffic. Beyond that, the Cybersecurity Act of 2015 gave companies including ISPs broadened powers to conduct surveillance. The point is: at this stage, it takes robust tech at scale to really change the status quo on surveillance, and Private Relay is perhaps the most promising example of this to date.

In a world full of privacy violations, like Clearview AI (which scrapes social media sites to sell facial recognition services to police) and DNA databases like AncestryDNA and 23andMe (where your relatives can out your own DNA by volunteering their own), Private Relay is like being given a glass of ice water in hell – to crib a Steve Jobs’ line.

It’s impossible to quantify how much customers will benefit by having all their internet histories shielded from ISPs, but it’s fair to say it will upend a major component of the current surveillance regime. It could, and should, permanently revert our expectations of privacy in many countries around the world.

Like this article? You may be interested in another I recently wrote about Apple! I’m trying my best to write thoughtful blog posts, and I would be very thankful for your support! Key Discussions now has a Patreon page, where you can generously help me. If you would rather support my work through a one-time tip via Cash App, that would also be greatly appreciated!

Thank you for reading, and please share and discuss with your friends and coworkers! And then check out the lively discussion on Reddit or the growing one on Twitter. Cheers – Spencer